northern studies

The series explores the realities and projected fantasies of Northern isolation using Canadian pianist Glenn Gould's experimental 1967 radio documentary The Idea of North as a scaffold and guide.

Northern Studies

by Bartholomew Ryan

In 1967 the legendary Canadian pianist Glenn Gould made a documentary radio program entitled The Idea of North. Fascinated by the uppermost fringes of his country, and the myths and romance that were a byproduct of their very remoteness, he recorded five individuals with experience in the region and widely divergent positions on it. Treating the voices as instruments, and the program like a score, he wove the elements together accompanied by the sound of a train, as if all the participants were sitting together aboard the Muskeg Express, embarked on the 40-hour journey from Winnipeg to Churchill, Manitoba, on the shores of icy Hudson Bay. The result was part contrapuntal fugue, part meditation on human nature, a portrait not of a real place but of the solitary retreats of human experience. Many years later, Minneapolis-based photographer Justin Newhall has taken up Gould’s project as a scaffold on which to construct a new series of photographs. The series is the product of the artist’s visits over the past few years to the port of Churchill, once an outpost on the fur-trading route, now largely a destination for tourists seeking the Aurora Borealis, or eager to spot polar bears who flock to the bay to hunt seal in the fall.

If Gould’s documentary captured the ways in which the North became a screen on which people projected their fantasies of escape and rebirth only to come up against the harsh reality of an unforgiving climate and the complexities of combining rugged individualism with the community spirit necessary for survival, Newhall treats such desires as so many aftermaths. The continued evolution of the region is a given in work that focuses nevertheless on the ghosts, taking the idea of north as an allegory for the condition of living, always already fading from vision, drifting into the wilds of disintegration and irrelevance.

That Newhall titles his exhibition Northern Studies, the name of an academic branch prominent in the universities of Canada and Alaska, is in part an observation on how various institutions (the academy, the state, certain strands of photography) collect and distribute knowledge with an apparent documentary autonomy. If the history of the North has been anything, it has been a series of miscalculations by interests propped up by the authority of the Academy or State, from fur-trading companies to Indian agents, entrepreneurs, scientists, and military research groups. Churchill is a palimpsest, performing this history of expansion and contraction, of reevaluation and redirection.

Since the late 20th century, documentary photography as a field has been problematized by an evolving understanding of how the “reality” of a given image is heavily determined by ideologically constructed framing devices. This devaluation of the authority of the image has become something that every photographer who works within or around this tradition must confront. Newhall’s exhibition title is a wry acknowledgment of this legacy, placing his project directly within a dubious history of research and anthropological investigation that has helped shape the North. It is the artist’s self awareness that affords the photographs a degree of integrity. They proceed according to Newhall’s lyrical-political sensibility. Rather than serving as a metaphoric final report accompanied by a series of weighty conclusions and proposals, they operate as open-ended meditations, marking the artifacts of a shifting social fabric at the extremes of human endurance.

Newhall’s first trip to Churchill was by train. There is no way to drive to the port from other parts of Canada, though once there it is possible to traverse a narrow network of roads. By design then, Newhall’s range of subjects was limited and not predetermined. While taking The Idea of North as a guide, he did not want to literally mirror its content. He could, for instance (a la Gould’s five narrators), have photographed five eccentric characters from Churchill’s 900-strong population, but instead attempted to capture the spirit of Gould’s contrapuntal form, seeking through an accumulation of divergences to manifest his own body of work.

Newhall shot primarily with a large-format, 4 x 5 view camera beginning at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. Repurposed from an era of cold-war investigation, the building serves as a way station providing lodging and logistical support “to scientific researchers working on a diverse range of topics of interest to northern science.” Many who stay at the center study the Aurora Borealis, which makes no appearance in Newhall’s project except by way of the poster tacked to the wall in Northern Lights, Northern Studies Centre, Ft. Churchill, MB. The work displays an underlying observational humor found in many of Newhall’s photographs: Star Wars videos sit atop a government-issue desk, luminous constellation stickers are affixed to the side of a blue stairway that leads to a viewing station from which the actual Northern Lights can be seen. The details point to the transient nature of the setting: left-behinds from various visitors, mild efforts at homeliness, suffused with a banal pseudo- scientific aura.

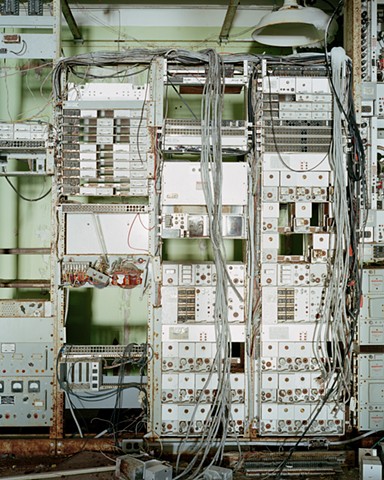

In a very different visual register, though continuing the theme, Cold War-Era Radar Facility, Near Churchill, MB bears witness to the region’s decline in global tactical relevancy. The wasting circuits and rusted frames of what seems a distinctly analog military era are shot with a centered frankness filled with a clarity that verges on the typological. This indexing tendency comes through concretely in Newhall’s images of Spruce trees. Spread across the windswept tundra between Hudson Bay and the Boreal forest, the trees are stunted by the extreme weather and short growing season, often reaching no higher than a tall human though they may be many years old. In Spruce (No.22), apparently shot at dusk, the ravages of the wind are clear: one side of the tree has virtually no foliage. The trees have an anthropomorphic quality, functioning almost as stand-ins for the human body. Read this way they become testaments to the tenacity of human survival in the face of extraordinary hardship; they also describe the individualism that drives many to the region, and traps them there.

Perhaps the most harrowing period in Churchill’s modern history, and indeed Canada’s in general, was a failed 1960s government experiment that forcibly relocated the 300-strong Dene people from their ancestral hunting grounds in the north to a location 10 miles from Churchill. Divorced from the land which had sustained them for generations and dependent on peripatetic government handouts, the tribe turned upon itself in a cycle of alcohol addiction, poverty and violence that resulted in the death of one third of its inhabitants over one decade. Deserted since the early 1970s, the location known as Dene Village was visited by Newhall. Walking through the foundations of a home, he came across a package wrapped in black plastic garbage bags secured by duct tape. Unwrapping it he found a stack of 8 x 10 glossy fetish shots depicting clothed women with impossibly large breasts. Newhall re-photographed the prints on location with his field camera, requiring so much concentration to set up and focus that he brought along a friend with a shotgun to protect himself from the very real threat of a bear attack. The 8 x 10s, aged through successive freeze and thaw cycles into a washed-out cyan, are transformed in this process from seedy props to aura-filled relics. Having finished with the original photographs, Newhall placed them back where he found them. Twelve of his prints are collected in the Dene Village Portfolio on view in this exhibition. Looking through the series has an intimate quality. For me, the women’s personalities have outlasted the objectifying purpose of the original images. The subjects seem patient in their long journey towards eventual breakdown.

One of the three virtually monochromatic white prints on display, Whiteout (No. 2), contains a faint outline of a machine on giant wheels approaching from the distance. The thing might be plucked from a science fiction film, a remote planet on which some hero is deserted, or a post-apocalyptic vision of an ice-aged earth. In fact it is a tundra buggy, a souped-up tourist bus returning from a trip across the icy plains to view polar bears. Within the economy of decline mapped out by the other works in Northern Studies, it is tempting to imagine this the last tundra buggy returning from a sighting of the last polar bear. “I began to get the impression,” says a geographer in Gould’s documentary, “that the North is a land of very narrow, very thin margins.” It is hard to imagine a photograph that could better capture the complexities of such a statement.